Shaping of Home

- Kaleb Bass

- Sep 16, 2019

- 12 min read

Updated: Mar 23, 2020

Selections from Signal Fire Trip Journal

July 15th to August 10th, 2019

Kaleb Bass

During the summer of 2019 I spent a month backpacking around the Rocky Mountain sub-ranges on a juried art trip with a the Portland-based organization Signal Fire, two great leaders, and a group of eight other artists. The theme of the trip was Waiting for Salmon, a topic resonating with my deeply rooted connection to the Salmon River, the significance of native salmon in shaping and supporting the place I consider home, and the threat to the continued existence of this ancient and important population. We visited locations on all sides of my "home range." We trekked into the Eagle Cap Wilderness in the Wallowas for the first week, hiked along the Selway River the second week, ventured into the Bitterroot Mountains the third week, and passed the last week in the North Cascades. Each of these locations lies within the Columbia River watershed, near the southern, eastern, and northern edges of the expansive drainage. These places also make up the reaches of the homeland of the Niimeepuu or Nez Perce Tribe—a range closely related to my personal and familial view of home. Other locations we visited included Umatilla, Cayuse, Coeur d’Alene and Bitterroot Salish Territories.

As a collective group of artists interested in how humans fit into the greater-than-human world, we shared invigorating discussions, read inspirational written works, and created meaningful art specific to the interior Northwest. In an attempt to capture some of the abounding inspiration and meaningful moments of the trip, I journaled nearly every day. Following are a selected few of those journal entries and images from the trip:

Week I: Eagle Cap Wilderness

July 18, 2019: Last night, as I lay parallel to the Earth and sky, I prolonged taking out my contacts for what seemed like most of the night.

Time seemed to speed by as the nearly-full moon ascended above the two jutting peaks to the south, like a fish leaping from the froth of a falls. Clouds sped by from the northwest to southeast, a migration of salmon single-mindedly set on their destination.

The only perceivable traces of the time-centered, technology-driven world outside this glacial valley were steady moving satellites and blinking airplanes, disrupting the rhythm of the moon and clouds. While everything seemed to be on fast-forward, the time on my watch (tucked in my boot beside my head) didn’t interest me in the slightest.

As my sleepy eyes focused on a spot in the sky, my viewpoint seemed to ascend above the trees. The stars appeared to move together, like a cluster of satellites drawn to an electromagnetic field, while the clouds in my field of view remained stationary. The streak of shooting star dropped me back down to the large granite rock where I lay wrapped in a sleeping bag, the Wallowa mountains, and the night sky.

July 20, 2019: As we walked back to the trailhead today I moved through the line of newly experienced backpackers like a bead alternating between every position on a string. I shared some conversations with the fellow artists I had come to know over a week in the backcountry of the Wallowas. While moving between gaps in the string of hikers, I also took the opportunity to reflect on the moments that led me to this place.

As I walked and contemplated, I plucked three long strands of bunchgrass from along the trail and began to mindlessly braid. My hands recognized the familiar movements just as my feet seemed to independently navigate the trail, leaving my mind free to drift.

The weaving strands—each wrapping forward before fading to the back—reminded me of the interconnectedness of present events with both my sense of place and history. After covering some distance on the trail, the braid swayed in front of my oscillating knees. Looking down the long woven strand, I realized how extensively my past and sense of place have intertwined with who I am.

I tied the now unified strand in a loop and placed it over my felt hat. There is a chance this hat has been in these mountains many years ago. The hat was my grandfather’s, given to me years before he passed. Only recently have I started wearing it as I explore the places my family has called home for many generations.

I will keep this band of grass on the hat as I walk along the Selway River next week, a trail this hat has also possibly known. Then perhaps when I walk out after week two, I will add a Selway braid alongside the Wallowa braid, weaving together the places I go with memories of the past and present.

Week II: Selway River

July 22, 2019: I have stood on this sand where I now sit writing, but the water flowing near my outstretched legs is different than when I was here last October, different than it was when I sat down a few moments ago, and different than it will be when I return this fall.

The Selway River is a special place. While my deep ties to the Salmon River pull me southwest toward deep murky pools, the Selway’s seemingly transparent waters invite me to stay. The water at my feet does not journey by my home on the Salmon, nor does the Salmon send currents to shape the expansive beaches of the Selway. The waters of these rivers do, however, mix eventually. The Salmon wraps its way around the Joseph Plains before joining the Snake River. The Selway joins with the Lochsa to form the Clearwater, and connects with the Snake near the town of Lewiston. Together these rivers—draining an enormous expanse of Idaho’s wilderness—unite to face the obstacle of four concrete behemoths together, powering toward the Columbia River and then the Pacific Ocean.

Tonight, the Selway feels like home. Perhaps it is the familiar colors of mountains and trees in the fading light of evening, the saccharine vanilla smell of Ponderosa Pine, the feel of hot sand and a cool downriver breeze, and the sound of water picking a path over rocks on a mission to meet with fellow streams.

July 23, 2019: The seemingly eternal sound of water spilling over, around, and through smoothed rock has been so engrained as a backdrop to my every formative action and thought that without it, a piece of me feels missing.

If I close my eyes and let my imagination take over, I can still distinguish the sound of the Selway from Slate Creek and the Salmon River, the ever-present white noise of my childhood. Yet the sound has the same invigorating effect on my mindset— I can think clearly, create more, be at peace.

July 24, 2019: Two nights ago, I sat on the downstream end of a large sand beach finishing my journal entry for the day. The tarp I have been drifting to sleep on under the stars for the past week spread out beside me, tonight not folded in half, but rather stretched out to a full seven foot square. I paused my writing and pulled my sleeping bag and pad over to make room as a friend made her way across the beach, sleeping bag and pad over one shoulder. A few moments later, another friend folded her foam pad out next to the tarp. Then another two joined the row forming along the bank of the river. As the fifth companion sat down, I tucked my journal away and enjoyed the company as the daylight faded.

Last night, only one brave soul joined me on the beach. Earlier in the day a rattlesnake made a crossing of the beach and found a small rock overhang on the edge of the sand to call home for the night. I imagine the apprehension of sharing a beach with a fork-tongued neighbor will soon again be overpowered by the draw of the clear night sky, pleasant breeze off the water, and waking to unobstructed rays of face-warming sunshine.

July 26, 2019: The hike back down the Selway today means the trip is nearing its halfway point. As I walked along above the smooth waters—which mirrored the trees across the river—I reflected on the first two weeks of this trip. A week in an area of the Wallowas where I had never been, and a week on the Selway River where I have been before, offered plenty of opportunities to share what I know, love, and respect about these special places. The luxury of being a participant is that I can enjoy all the questions, conversations, and shared experiences that are so rewarding as a guide, but without the added pressure of planning logistics and other necessary responsibilities of leading a trip. Thank you Ryan and Kerri!

As we follow the flow of the river out to the trailhead, an attempt to keep pace with a formation of bubbles on the fluid surface below is like trying to hold on to experiences as they happen. Before the bubbles make it around the next bend in the river, catch in a cycling eddy, accelerate into a churning rapid, or vanish on the glassy surface—my focus drifts back to the origin of the bubbles upstream. Rather than grasping at fluid traces, I appreciate the presently passing currents as my strides along the trail quicken and slow independent of the river’s pace.

Week III: Bitterroots

July 27, 2019: Today we hoisted our packs to the top of the van and drove across the Bitterroot Range to another state and a new time zone. Traveling by car always feels disorienting after a week traveling on foot or by raft, the pace accelerating faster than a mindset accustomed to the backcountry tempo can keep up with.

I have never been big on arbitrary political boundaries inked on a map, even before I really understood them. As a child full of curiosity about the world around me, I remember rafting the lower Salmon River and coming to the confluence of the Salmon and the Snake. The sun-faded river map now showed Oregon on river left and Idaho on river right. Setting up camp on an Oregon beach felt and looked no different from an Idaho beach. Yet it made sense that this powerful river—as it carved the deepest gorge in the continent—would make as good a border between states as any. Far less sense could be interpreted the next day when a straight dashed line on the map, not corresponding to any drainage or other physical feature, indicated the canyon wall on the left was now the state of Washington.

Time zones made more sense in theory. As the sun traveled across the sky and disappeared over the mountains to the west, understandably the places in that direction would have daytime later into the evening. If I scrambled to the top of that mountain I could even catch a few more rays of sun long after sunset in the river canyon below. Following Highway 95 a few miles up the river and crossing over a bridge due south and “losing” an hour confounded this initial understanding of boundaries established by the sun.

I look forward to approaching this week in a new place with the inquisitiveness I had at the age when everywhere I ventured was full of unknown possibility. Attentive curiosity may not provide the answers to where government officials determined borderlines on a piece of paper, but maybe close observation will reveal a deeper understanding of other systems and phenomena.

Aug 2, 2019: After feeling so at home on the Selway last week, strangely I feel somewhat out of place here in the Bitterroots. The weather still comes over the mountains from the west—but the clouds have a different energy. The dark, heavy thunderheads unleash hail the size of thimbleberries. Rivers and streams seem to flow in the wrong direction. It amazes me that these waters still find a way to navigate around the jutting peaks to the west and join the familiar waters from the Salmon in the Columbia before flowing into the ocean.

As I hiked further west into the Bitterroots, back toward familiar mountains, I began to realize what constitutes the boundaries of place to me. I feel most at home in mountains where water drains to the Salmon; I feel close to home in places where waters make their way to the Snake. This place represents the far reaches of home. The water at my feet flows east and north, through several unfamiliar rivers, across the depths of a lake that could submerge seven of the tallest trees in the area end-to-end, through human-made dams, and across an international boundary, before joining the Columbia River—closer to its headwaters than to the ocean.

Drainages connect valleys and canyons. They shape the landscape, carry nutrients, and hydrate all life. And for me, this network of rivers and streams establishes an underlying and very physical sense of place in a world broken by intangible borders.

Week IV: North Cascades

Most of this week I devoted my energies to install, contemplate, and write descriptions about canvas sculptures (see week four below)—a project culminating ideas from throughout the trip.

Projects

During the first week of the trip (in the Wallowas of Eastern Oregon), I thought a lot about the idea of collaboration with the environment and the importance of rivers. As rivers ultimately are shaped as a collaboration between rock and water, I was drawn to collaborate with a rock, stream water, and a dye made from plants gathered in the area. In this experiment, the shape of the rock and the flow of water ultimately had more control over where the dye went than I did. Each layer shows the depth of the landscape, but rather than topography, the contours represent the bands of nourishment the landscape receives from the surging artery that is the stream.

Week two I was drawn to consider human relationships with the landscape and how we move through it. I explored time-lapse in the style of previous three-channel video pieces to show the journey along the trail. On the last day on the Selway, I invited my companions on the trip consider and share their morning at camp through a video piece. The prompt was simply to attach three cameras anywhere on their body with the majority of the frame showing their environment. After 5–15 minutes they handed off the camera to another person. The unique placements and angle of the cameras prompted attention to new perspectives of places and activities. The feedback from my peers after the activity was extremely useful in considering how I move forward with this body of experimental video.

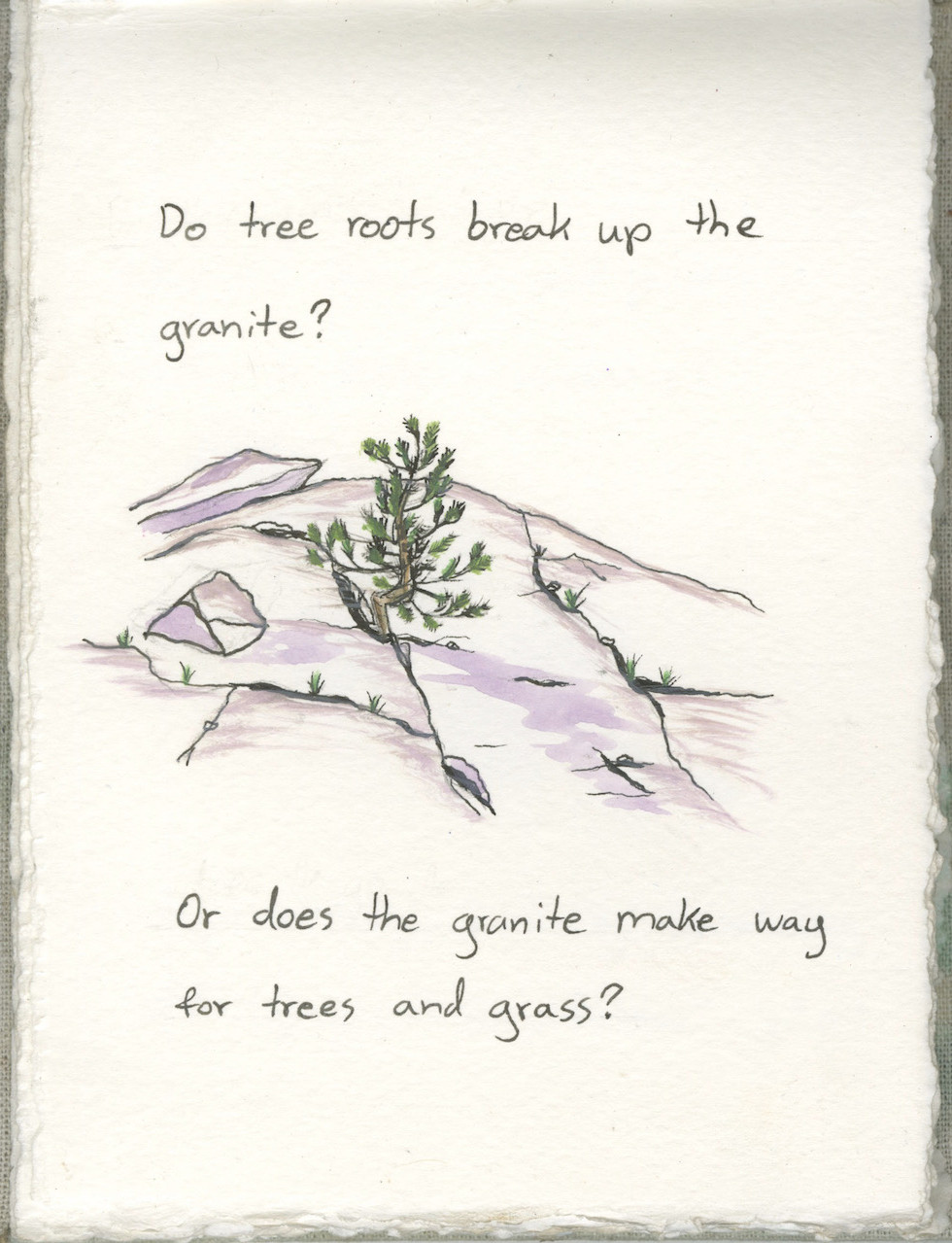

As written in my journal (July 27), the focus of week 3 was inquisitiveness, attentive curiosity, and close observation. I turned my journal entry from July 31st into an illustrated story in a handmade sketchbook. Most of the drawings were completed in an evening and the following day from observation at locations a short walk from camp. I added the text and color while seeking shelter under my tarp from the alternating rain/hail showers and sunshine that defined the week at Tamarack Lake. Though a new format for me and quickly executed, this project was unexpectedly enjoyable and the process of sketching and painting was certainly a highlight of the trip.

Week four included some solo days to think about and create more elaborate pieces. I packed in six yards of 63" canvas in to create temporary installations.

An intention in my artwork is to recognize the landscape as more than a passive backdrop for art, recreation, and life in general. For these canvas sculptures, I invited the wind and sun to collaborate as active contributors in shaping and lighting each piece. However today, both were a little too enthusiastic to help out. I abandoned my first piece on the hot rocks to begin another piece deep in the cedars. The eager wind whistled through the treetops exposed to the sun above, but on the needle-blanketed ground a light breeze wove through the giant trunks and skipped between cool shadows.

As I unraveled each individual thread from the edges of the canvas, I had ample solitude to reflect on the past four weeks—the people, the places, and the experiences shared with both. The largest piece, a sheet roughly the size of the tarp I have been sleeping on for the past month, took me more than a full day to complete. The canvas slowly took on the shape of the river valley and mountains outside the cedar grove where I threaded and tied strings over low-hanging branches.

The piece questions how the landscape of this area is continuously formed and reshaped. A towering cedar supports vertical strings, suspending the canvas landscape from above. Twisted into these strings—small objects such as pinecones, leaves, feathers, and a beehive represent some of the plants and animals that play a role in altering the landscape. The wind through the trees from upriver lightly ripples the ridges in the fabric and floats needles into the folds. Under the canvas, strings weighted by decaying needles, a beaver chewed stick, a deer vertebra, bear and deer droppings, and hardware from a washed out bridge represent some of the factors that shape the landscape from below. In a dynamic system that is being pulled and shaped from various directions and by many influences, how do we settle our weight into the complex configuration without snapping strings or tearing holes?

Mishaps—A metallic flash glinted though patches of sunlight as it arced through low-hanging cedar branches. Moments earlier I heard cottonwood leaves upriver warn of the impending gust. I looked over my shoulder just in time to see the corner of the partially suspended canvas, where I had placed my only needle, flip upward and send the needle toward an immense pile of driftwood. I searched through the driftwood and sand for quite some time before sitting down and staring at all the strings I still had left to place. After a few moments of defeat, I picked up a small green cedar branch from beside my feet and took out my pocketknife.

Progress on the installation proceeded a bit slower, but in the end no one could tell what type of needle threaded each string. However, for me the cedar needle added a quality to the piece that I would have otherwise missed out on.

Thank you Signal Fire, Tarp and Kez for putting together such an incredible trip! Thanks to the eight other artists for all the great discussions and moments shared over a month in the backcountry!

And thank YOU for reading!

Comments